Eric Bell (Thin Lizzy, solo) • Hit Channel

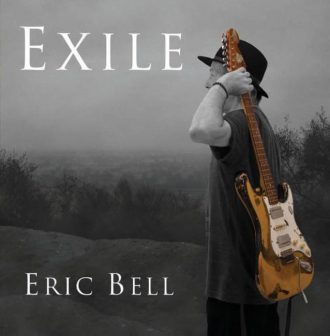

HIT CHANNEL EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: April 2017. We had the honour to talk with a great guitarist: Eric Bell. He is best known as the original guitarist of Thin Lizzy, playing in their first three studio albums. He has also played with Them, The Noel Redding Band, Mainsqueeze and Bo Diddley. He has released many albums with The Eric Bell Band. His latest solo effort is “Exile” (2016). Read below the very interesting things he told us:

Are you going to record anything in the near future?

It supposed to happen in mid June. I will be going over myself to do it. I recorded “Exile” last year. It’s the first album that I recorded on my own. It was like an experiment. I wrote songs and recorded them on a 4-track machine like demos. I liked the way they sound. There is an atmosphere on them. With The Eric Bell Band when I called musicians in the studio with me, I couldn’t get that atmosphere that I got at home, on my own. So, last year I did an album called “Exile”, and I did it on my own. So, I will be doing that again this year.

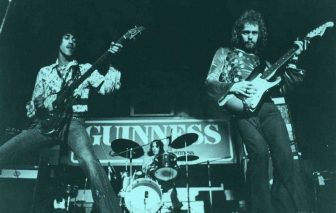

How exciting is it to perform in 2017 the music you created with Thin Lizzy 45 years ago?

(Laughs) It’s a long time ago. For a start, a lot of people think that Thin Lizzy is the line-up that included the twin guitarists. There was much talk about Thin Lizzy with the two guitarists, but very-very little about me. About 2-3 years ago, Universal Music phoned me up and said that they wanted to re-release the first three Thin Lizzy albums that I was on. Since then, there is a lot of nice talk about my work on these three Thin Lizzy albums. So, I think that’s a nice thing.

How important was the tour with Slade to the later career of Thin Lizzy?

It moved us up then. We, Thin Lizzy, played in clubs and pubs that held about 300 people and then we started doing the Slade tour and there were thousands of people. We couldn’t believe it. The three of us walked on stage and there were thousands of people. And upstairs, in the balcony. Everybody was there to see Slade and they gave us a real hard time. We couldn’t really cope with this because we used to play just the songs and we didn’t really put on a show. But whenever we saw Slade, they were there to do a show instead of playing music. I think that wake Philip (ed: Lynott –vocals, bass) up. Philip started to become more conscious and more dramatic on stage.

Did you expect that the “Whiskey in the Jar” (1972) single would become so popular?

No. We were rehearsing in a pub in London. There was nothing really happening out there. We tried to do some original songs that were in the works. So, Philip started messing about singing all these Irish rebel songs and then he started singing “Whiskey in the Jar”. Myself and Brian Downey (drums) were playing along with him, just as a joke. Our manager (ed: Ted Carroll) walked in. He had a new amplifier for me to try out. We all stopped then. We were looking at the new amplifier and our manager said: “Oh, what was that song that you were just playing before I came in the door?” Philip said: “We were just messing about” and Ted said: “Yeah, but what was it?” and Philip said: “Oh, it’s ‘Whiskey in the Jar’ ”. He said: “You had your first single to record for Decca in about six weeks. Have you got an A-side?” and we said: “Yes, ‘Black Boys on the Corner’”. “Did you have a B-side?” “No, not really”. “Why don’t you put this as B-side?” But anyway, six weeks later when we were in the studio, we did the A-side “Black Boys on the Corner”. We sat on the chairs and said: “What are we going to do now?” Our manager was there and said: “Why don’t you try Whiskey in the Jar?”. Myself played acoustic guitar, Brian played drums and Philip played acoustic guitar and put vocals on it. They asked me to put some guitar on it and I didn’t know what to play. They gave me a cassette and I had to work on that song. I worked on that for six weeks before I came up with the intro of this song. They released it and it started taking off, you know. It was no.1 in Ireland and no.6 in England, and it was a success all over Europe. Things went really well.

One day Metallica called you and asked you to play “Whiskey in the Jar” live with them. What happened next?

One day Metallica called you and asked you to play “Whiskey in the Jar” live with them. What happened next?

Yeah, they phoned me up and they sent a car to pick me up and take me to the Marble Arch in London, I was living in London then. I went to their hotel where it started a convoy of vehicles that went to an Army camp about 30 miles outside London. They had a private plane and they flew to Dublin. I had to stay in the changing room on my own for two hours. They played for that long. Then, I went on stage to play “Whiskey in the Jar”. It was a very strange night. And the fuckers didn’t pay me (laughs)!

Are you frustrated when some people ignore the first three Thin Lizzy albums?

Not too much today. But as I said earlier, Universal Music re-released the first three Thin Lizzy albums. That was a good thing to do. Because there are a lot more people that they know about the early Thin Lizzy now, because of the re-releases. But there are still some people who probably don’t know that there are three Thin Lizzy albums out there.

What made “The Rocker” (1973) song so special?

I don’t know. It’s very raw. It’s very raw as far as the guitar. It has that raw three-piece rock feeling. Its chord is probably A major, and it sounds like something good. I can’t sit down and try writing songs to make a lot of money out of it, you know. It’s just the way we recorded it and we released it. It became a very strong live song. As we were standing on stage, it felt good.

Was it inevitable for you to leave Thin Lizzy?

Well, we were all very young. At that time, I was 22-23. At the start of Thin Lizzy, before we went to London and before “Whiskey in the Jar” was a hit, we lived in Ireland and I loved this. I thought it was fabulous. Everything was good. But when we went there and started becoming a bit commercially successful, there are a lot of things that go with that. You were told what to wear, what to do. Our manager told me that my guitar solos were too long. “It’s not your fuckin’ business. You are in music business and I am a musician”. It was excellent and then we moved to London. Everything changed. We all lived in a big town and we knew nobody there. We had to start right from the very bottom again because no one knew who Thin Lizzy was. We had to start form the very bottom all over again. Then, there were a lot of drugs and drinks and… LSD (laughs). I just had been through a very bad time. Then, I tripped out on anything I could find because my girlfriend left me and so on. Everything started becoming unreal, like a sort of a circus. I took that as a warning in a way: “You had to leave”. Philip is dead, I would be dead and Gary Moore is dead. It shows you that the rock ’n’ roll lifestyle can be very dangerous for some people.

What was Phil Lynott like on stage and off stage?

What was Phil Lynott like on stage and off stage?

When I met Philip first he was a very soft-spoken guy. He was a really nice company. We got a house together, so I got to know him pretty well. On stage, Philip was trying to find himself. He tried different clothes: denim shirts and then leather shirts, leather trousers. All different kinds of clothing, different kinds of bass guitars with pearls on them. He was trying to find a stage image. Then I left and his stage image completely changed. He wore leather rather than denim. He started armbands and those kinds of stuff. That’s the direction he went. There are two different times. When I first met Philip he was a normal type of guy and then I left the band. Years later, I met Philip again, it was a different Philip. Of course, everybody is changing.

Do you like the music of Thin Lizzy after your departure?

Not really. No. As far as I was concerned, it wasn’t Thin Lizzy. It’s just the same name, not the same band. It’s a different band. Don’t get me wrong, they were excellent on what they did, but it doesn’t appeal to me.

Do you have happy memories of the period you played with The Noel Redding Band?

No. When I met Noel (ed: Jimi Hendrix Experience bassist) first, he was living in Cork, Ireland and I was living in Dublin at that point. Anyway, he asked me to go to Cork and meet him. I was very starstruck because he lived in a big house. He looked that far: The paintings inside, the snazzy sort of clothes. He had a beautiful sports car. I liked that type. The thing was, I thought it was gonna be a three-piece band but it turned out to be a four-piece with a keyboard player (ed: Dave Clarke) who wrote most of the songs, which I didn’t really like. I found it very difficult to fit in musically. Then, Noel became very stoned, very drunk and get very cynical and a complete nasty. But I stayed in the band because they were going to tour in America and I hadn’t been to America. I wanted to go to the States and play. But after the band broke up, myself and Noel became very close friends and we played together for very long, with different drummers. Yeah, at the start of the Noel Redding Band it wasn’t very nice, but after a few years I got to know Noel well and we became very close friends.

What was the most important thing you learned when you played with Van Morrison in Them?

Going on stage with Them. I had a list of songs that we had rehearsed and we were supposed to play. The first night I had a gig with Them, I looked at the list and it was “Baby, Please Don’t Go”, so I was ready to play that intense riff and Van turned to me and said: “Start a blues in E, man”. I said: “What?! What about the list?” He said: “Fuck the list. Start a blues in E” (laughs). I only did about 8 or 9 gigs with Van, before he went to America. We just didn’t know what he was going to do: He would just stop a song in the middle and start another one that you never heard before, so you really had to be on the boat. That was a great experience for a young guitarist then.

Was it an interesting experience for you to tour with Bo Diddley?

Was it an interesting experience for you to tour with Bo Diddley?

Yeah. Bo was always a lovely guy, a real gentleman. One of the pioneers of rock ‘n’ roll. He was such a nice man and full of life. He was about 60, I don’t know, 64 years of age when I was working with him. I learned quite a lot from him. As I said, he was a real gentleman. Full of life, enjoyed his life and laughed a lot. Very nice guy.

Could you imagine your life if you had never listened to Lonnie Donegan?

(Laughs) Way back in 1957, I still had no television in our house in Belfast, just a big old-fashioned radio. The radio was on nearly all day and it used to play very strange, very square things in those days. There was no rock ‘n’ roll, so it was all middle of the road music. One day, I think I was doing my homework for school and it put this record on -I think it was the “Rock Island Line” or “Gamblin’ Man”- and I was just shocked: “Wow, what is this?!” and this guy was singing his heart out. I really went insane. It was so exciting. Really exciting. It was something I hadn’t heard before. I just listened and listened and the guy mentioned his name: “Lonnie Donegan”. I said: “Right! Right! I ‘ve got to hear more of this guy”. I hadn’t bought a record player, I had some school friends and I would go to their houses after school and in one of the houses I went, on the floor, there was a Lonnie Donegan album. “My God! Wow! Put it on!”, I said to this guy, Jimmy, and he put it on. It changed your life, you know. The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Van Morrison, so many people were influenced by Lonnie Donegan.

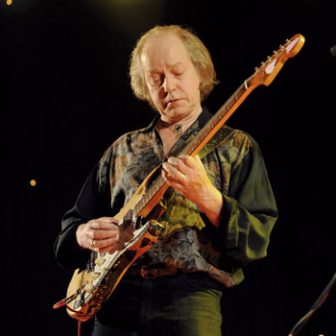

Gary Moore replaced you in Thin Lizzy and in some other bands. Can you describe to us your relationship with Gary?

Gary and me were very close, very good friends. On the “Exile” album that I released last year, I did a song called “Song for Gary”. That’s a very true story that I mentioned. At that time, I was with a little band from Belfast called the Deltones and we played in Hollywood in Northern Ireland. That was the first time I met Gary Moore and he was about 11 or 12 years of age. He was a fabulous little player and really-really talented. He liked my playing, so we used to go and watch each other. He was in another band. Then, I left Deltones and he joined. And then, a few years later, he was in a blues band called Shades of Blue, he left and I joined. So, he was joining the bands that I left all the time, even Thin Lizzy. I left Thin Lizzy and he joined. He was a very good friend of mine. I really miss the guy. I really do. I was living in London, it was about 7-8 years ago, and Gary was living in Brighton and I used to go and stay with him for a few days every 3 or 4 months. I would play guitar with him and have a few drinks. He was a really nice guy and I really miss him. A superb guitarist in history.

Can you please tell us the story about Eric Clapton when you and Noel Redding supported Freddie King?

Can you please tell us the story about Eric Clapton when you and Noel Redding supported Freddie King?

Ok. That was in Los Angeles. We did about 6 or 7 dates in a row. I think it was at a club called The Roxy in Los Angeles and Freddie King was every night on the top of the bill. I watched him every night, he was absolutely amazing. Anyway, I made a few friends in Los Angeles, among them, it was a black bass player. We played six nights in a row in this club, and on the seventh night I wanted to go back to the hotel, because I was a bit tired. The bass player said: “Hey man, no, don’t go back to the hotel tonight after the gig because you are tired. Do you know who is coming down tonight?” I said: “No”. “Eric Clapton”. I said: “Yeah, of course” (ed: in an ironic way). He said: “No no, seriously”. Then I thought that this is America. Freddie King was one of Clapton’s favourite guitarists, so we did our show and then I went to the bar hanging out with a few friends. About ten minutes later, this guy walked on the stage, he set up an amplifier, put a chair on and put on a black Stratocaster and fit it on the chair. “Wow, what was that?!” About 20 minutes later, Freddie King walked on again, Noel Redding was playing bass, Buddy Miles (ed: Jimi Hendrix’s Band of Gypsys) was on drums, some sax player and then Eric Clapton walked on and he was out of his tree. He didn’t know where he was. He probably was on heroine or drunk. I don’t know. Anyway, they started playing and I was behind the stage watching all this and Clapton couldn’t play two notes. He couldn’t even stand. Freddie King walked to his side teasing him and playing a few blues licks and Eric Clapton looked at him and shook his head. Then, they started a slow blues and the same thing: he couldn’t play. So, in the end of this, Clapton stood up, put his guitar on the chair and went backstage where I was. I was sitting on these stairs, that led up to the changing room upstairs. I was standing there and Clapton walked up to me. I was watching him walking upstairs and he said: “Excuse me, man, can I go upstairs?” As he was walking upstairs, I poked him with my hand: “Hey Eric, any chance to borrow your guitar?” He said: “No fuckin’ way, man” and he laughed. “No fuckin’ way” (laughs). So, that was it.

Do you think social media like Youtube and Facebook have helped younger listeners to learn about your music?

Yeah, I think it’s great. In the technological age, there are a lot of things that I don’t like, but it’s excellent as far as getting information. If you are a musician you can sell shows and people can book. All the information is there. For that reason I think it’s fabulous.

You have been in many tours and watched many concerts. Who was the most talented musician you’ve seen with your own eyes?

It’s hard to say. There are just so many. All the good guitar players, I think. All different kinds of guitar players like Rory Gallagher, Freddie King, Joe Pass the jazz man, Bert Jansch the folk guitarist. People like that.

Did you get to know Rory Gallagher?

Did you get to know Rory Gallagher?

Yeah, I knew Rory a little bit. He was quite secretive, you know. I met him one day in London, he was in Denmark Street, where all the music shops are. I was on the other side of the street, I saw a crowd of about 8-9 guys standing there and talking. I looked what was going on. I walked over and Rory Gallagher was in the middle of them. I said: “Hi, Rory” and he said: (ed: quietly) “Eric, don’t do it”. All the other guys buggered off and I said to Rory: “How are you doing? Do you want to go for a coffee?” So, he went with me to a wine bar and he said: (ed: quietly) “Actually, I want a glass of wine instead”. As we were sitting there, there was that muzak thing being played in the wine bar. And Rory said: “This music is an insult to my ears” (laughs). I think I understand a bit why this music was an insult to his ears. We sat down and had a bit of a talk. He seemed very drunk, he didn’t know where he really was. I left him after 20 minutes, I had to buy a toy for my son. I bought that toy and went back to the wine bar and he wasn’t there. So, I walked to Denmark Street, where is full of guitar shops and I saw Rory being inside one of these guitar shops. I went there, I talked to him again and I said: “Do you fancy another coffee or drink?” So, we went out of Denmark Street and went across Tottenham Court Road. There was another wine bar, just across the road. It was just 10 minutes walk to this wine bar. And he said: (ed: quietly) “Eric, where are we?” I said we are on Tottenham Court Road. I had to go home, so I said: “Listen, you are gonna be ok”, because he didn’t know where he was. I said: “Can you give me your phone number?” He said: “No, you can give me your phone number”. I wanted to phone him to know if he arrived home safe. I said: “Ok”, so I gave him my phone number and at about 8 o’clock that night he phoned me. He said: “Hi Eric. I’m Rory. I’m home. I told you, I told you, I told you that everything is fine. I told you that”. That was the last time I talked to him. It was about three years before he died (ed: he died in 1995).

A huge “THANK YOU” to Mr Eric Bell for his time and to Quique for his valuable help.

Official Eric Bell website: http://www.eric-bell.com

Official Eric Bell Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/EricBellOfficial